Mike Lane (Channing Tatum), the titular figure in Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike, is perhaps the nicest man I have ever encountered on screen outside of a Hallmark Christmas film. Although I initially found it easier to believe that a half-lizard man was stalking Manhattan’s sewers than that someone with Tatum’s looks could be so kind, I quickly realized that Soderbergh was using this hyper-sweetness against Mike. It’s the initial warning that he’s not your father’s hero. When Mike first saunters across the frame, he is nude. I point this out not simply as an excuse to include this gif but because it’s significant that Mike first exists as mere body. This body underscores his physical masculinity (he does in fact have a Y chromosome—a very, very nice one), but the film calls into question the cultural signification of this flesh. He may be male, but does this make him a man?

Since Simone de Beauvoir published The Second Sex in 1949 and drag queens burst onto the pop cultural scene in the 1990s, people have acknowledged that femininity is something you do, not something you are. As Judith Butler taught generations of gender studies majors, femininity is an act that must be continuously performed in order to have meaning. Masculinity, on the other hand, has mostly remained the default position. Men are assumed to be masculine—unless they act in an obviously feminine manner—and women who are not performing their proper feminine roles are immediately derided as masculine. Masculinity itself is, therefore, taken for granted, the natural gender at odds with feminine artificiality. With the help of a few rip-away pants and leopard thongs, Magic Mike attacks masculinity’s unassailable position by revealing that it is no less a performance than femininity. Indeed, in Magic Mike, masculinity is entirely a performance—one centered on money.In an interview with Elvis Mitchell on KCRW’s “The Treatment,” Soderbergh states that he is exploring the effect of unemployment and casual employment on masculine identity, arguing that job insecurity creates more than an economic crisis in men. It dismantles their identities, revealing the vulnerable beings underneath. Strippers then best exemplify the men of America’s Great Recession because they have been reduced to their barest selves.

When Mike first puts on clothes, he is wearing the uniform of a construction worker—the epitome of the traditional masculine provider hit hard by the recent recession. Haggling with a foreman who won’t hire union labor, Mike is told that this form of labor is too expensive and unnecessary in modern America. In the place of skilled workers, we find Adam (Alex Pettyfer), “the kid”—a former college football prospect (a casting choice which suggests Soderbergh has never seen a strong safety) who answers a Craigslist ad to tile roofs for minimum wage. After Mike fails to teach the kid to tile without stealing sodas from the foreman, he instead takes him under his wing at the Xquisite Strip Cub, wherein the kid learns that Mike’s construction uniform is just a costume. His SUV and spacious apartment are financed not by the work of his hands but by the thrusts of his well-muscled hips.

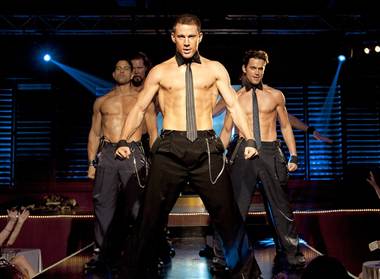

Run by the hilarious, delusional, and perpetually stoned former stripper Dallas (Matthew McConaughey), Xquisite features a crop of burly, waxed men donning the garb of traditional masculinity. These uneducated men would likely have been working in union jobs thirty years ago, but the shifting economy has left them without marketable skills beyond the ability to mimic mid-century American manhood. As I watched Mike and his band of men perform in the uniforms of fire fighters, police officers, soldiers, etc., I was reminded of the classic drag ball documentary Paris Is Burning. In 1980s New York, gay men of color transformed their identities not only by dressing as women but also by pretending to be soldiers, CEOs, and other masculine types. The Xquisite strippers similarly ape the clothing, postures, and even the speech of hyper-masculine men, but as the costumes come off to reveal fluorescent G-strings, the men, like the drag queens, shed the fantasy to reveal bodies bereft of meaning.

Soderbergh highlights masculine costume not only in the strip club but also in the seemingly banal scene in which Mike dresses in a suit in order to request a bank loan. A master of the wide shot, Soderbergh knows to use the close-up sparingly, so when he does, he is alerting the audience to pay attention. When his camera closes in on Mike buttoning his crisp shirt, smoothing his tie, and putting money into an expensive briefcase, the focus on the act of dressing reminds the audience of the care the Xquisite men take getting into costume. Mike flirts with the female loan officer, looking the part of the successful businessman. Nevertheless, this banker condescendingly explains that Mike is simply not a good credit risk regardless of the stacks of cash he has placed on the table: the computer rating system says so. In a world ruled by finance and credit, he is simply a bad score; thus, despite his expensive costume and his protestations that he is an entrepreneur, the larger economy deems him a body devoid of value.

Men outside of the stripping word occupy the fringes of this film because they inhabit a world that Mike and his friends can’t quite touch. With their college degrees and 401(k)s, these men represent a new form of contemporary masculinity where physical strength has been replaced by education. Presented as snobby, selfish douchebags, these men are no less caricatures than the police officers Mike and the kid impersonate, but the educated men’s act is backed up by real cultural capital. Even though Brooke, the kid’s sister, and Mike’s “friend” Joanna both enjoy Mike’s company, they want to date these consultants and financial advisors—men of the new information class. Highlighting Mike’s feminization, Soderbergh often shows him calling Joanna—a solidly middle-class woman graduating with a psychology degree—and waiting for her response like a stereotypical needy female. Joanna even tells Mike, only half jokingly, to simply lay in bed and look pretty—an idea she reiterates when he finds her at dinner with her fiancé and she pretends she barely recognizes him. Mike offers nothing but a beautiful body; he is not a man to be taken seriously.

This split between these two types of men climaxes when Mike and the kid perform at a sorority party, grinding up against young college girls as their boyfriends—clad in polos and upturned collars—look on from another room. When a fight breaks out between the strippers and the college boys, the thong-clad strippers—silly though they appear fighting with fake guns and flaccid billy clubs—still “win” because of their physical strength. Although this scene is primarily included to introduce a significant plot point, the narrative machinations are less interesting than watching the working class men attacking their social betters while arousing their girlfriends.

Soderbergh, in his interview with Mitchell, argues that female desire and fantasy define the male strip club and differentiate it from the standard girly show. While men go to strip clubs alone, imagining that they might actually sleep with the performers, women attend strip shows in groups (usually for bachelorette parties, 21st-birthdays, or other special occasions involving sashes and silly headwear) and raucously enjoy a fun and slightly embarrassing fantasy before going home to their husbands or boyfriends. Soderbergh stops his discussion of female fantasy here, but his film descends to a much darker place, highlighting the animosity between the performers and patrons. Women may enjoy objectifying and dehumanizing attractive men, but this doesn’t mean the men always enjoy the encounter even if they do end the night flush with a thong full of singles.

I’m obviously a proponent of women engaging in healthy sexual fantasy, and I’m supportive of sex workers’ rights, but I couldn’t help but be disturbed during some of the stripping, particularly the kid’s first dance. Walking on stage like a lost, frightened child, the kid awkwardly begins to remove his ratty, soiled clothes with trembling hands. I felt dirty—as though I were watching a homeless kid selling his body, which is exactly what the character is doing. When I later looked up clips of Tatum during his stripping days (don’t judge; I couldn’t help myself), I felt the same shame as I watched grainy footage of a skinny, young boy grinding against a filthy stage. We may pretend that male strip clubs are all about men making money and women having fun(!), except for the uncomfortable reality that actual human beings are offering up their sexualized bodies as entertainment because they have no better options.

Soderbergh subtly hints at the ugliness and hatred beneath the toothy smiles and practiced eroticism of the gyrating men. In the July Fourth performance, the strippers, outfitted in army fatigues, aim their groins like guns and fire at the audience with expressions of glee lighting up their normally dead eyes. Even though the women clap and hoot at the silly spectacle, one suspects that the aggression is not all for show. Such hostility is personified in Magic Mike’s final dance. Dressed in baggy sweat pants and a bulletproof vest—suggesting no masculine type, only pure aggression—Mike engages in a stunning performance of choreographed rage. He expresses anger at the audience, at the new economic world, and, most of all, at himself. Although he thereafter gives up stripping and earns Brooke’s respect, his life savings is still gone, and his future remains bleak. Perhaps Soderbergh is suggesting that Mike’s ability to connect with a women who desires him for more than his body could teach him a new way to be a man. I’d like to think so. But that rage will not easily dissipate.

I saw Magic Mike a day after seeing The Amazing Spider-Man, and I couldn’t help but notice that Andrew Garfield was shot in a decidedly sexual manner compared to the original Spider-Man’s g-rated images of Tobey Maguire. Lingering on Garfield’s skin-tight suit in numerous shots, the camera often objectified his form by cutting it into pieces as it closed in on his assets. Spider-Man was invented in the early 1960s out of Cold War fears of nuclear bombs and radiation just as Superman arose as a reaction to the Great Depression’s long lines of unemployed, powerless men. America seems to create superheroes—men defined by their physical strength—when the world is gripped by cultural insecurity. Magic Mike’s very name implies that he is a twenty-first-century parody of such figures, only he has been stripped of all his powers, including his dignity.

Excellent and informative